Do AI or die?

Another n-AI-l in the coffin?

There were some notable discussions on lawyers and AI, as the sun rose on 2025. It kicked off with a tweet by Andrew Wilkinson. He’s the co-founder of Tiny. They buy start-ups. It’s a sort of street food alternative to private equity fine dining. So he’s no stranger to shaking up complex and stuffy industries.

The smart people in the bubble quickly pegged this as a user experience problem ailing traditional legal services, rather than the death-knell for human lawyers. Yet most of the same pundits also concluded that lawyers should use AI, to keep up with client expectations.

That seems quite sensible on the surface. But lurking beneath those glib waters is a paradox - even a multi-headed paradox hydra.

Here are 5 key paradoxes that raise serious questions about AI and legal services: which way it’s likely to go and what lawyers should do in response.

Paradox 1: exploitation asymmetry

When they say lawyers should use genAI, they rarely specify how. Surely not like Andrew Wilkinson did. Why would a client pay a lawyer to do that?

So there is a critical asymmetry: clients can use chatGPT. In-house lawyers can use chatGPT. But law firms can’t use chatGPT in the same way. Why would a client pay for that?

If you break down most legal work into component parts, only a small part of the process is true “legal” work. The rest is client onboarding, fact-gathering, organising meetings, taking notes, research (not necessarily legal research), analysis (not necessarily legal analysis) and generating a document containing the advice.

So when we say that lawyers should use genAI, what are the Jobs To Be Done that genAI is good for? Is it for core legal work, or the practical and operational wrapper?

So the first paradox is Exploitation Assymetry: lawyers using AI does not necessarily mean (and most likely means not) using it for legal work as such.

Vendor behaviour will be governed by two ratios: value:preference and value:risk. Technology brings value when it removes the tasks you’re not good at or don’t like to do. Lawyers like legal and strategic work but don’t like the admin. So it makes sense that they will prefer technology that reduces the process burden - especially if they are not experts in process, UX or customer success. If it’s the core legal output that carries most of the value and risk, then delegating the higher-risk higher-expertise tasks to technology is less likely than delegating the process wrapper.

Paradox 2: the better mousetrap dilemma

It’s viable to say that lawyers who use AI in the process of delivering a legal service, will be more efficient, faster and will charge less. Especially if they use AI effectively in the process/transactional space.

But compared to who? Compared to those lawyers who ALREADY use proven processes, automation and user-centric design to ALREADY provide great advice, quickly and cost effectively?

Take contract drafting. A good template, in an automated workflow, offers certainty and repeatability with compounded speed over multiple interactions. It’s not obvious that genAI with its more limited repeatability offers any added efficiency - and I can see how it could offer much less efficiency. GenAI’s limitations (the need to prompt, review, correct) may not result in net gains. Alex Hamilton was equally unconvinced, commenting on Thomson Reuter’s claim that their AI product CoCounsel Drafting saves lawyers 50% of time - when doc auto vendors, legal designers and BPOs claim to save much more than that.

So the second paradox is the Better Moustrap Dilemma: lawyers who use genAI may well outpace the lawyers who don’t. But will they beat the lawyers who use proven (pre-AI) tools and methods to deliver a great legal user experience?

AI, even in the best-case use cases, may not be the better mousetrap.

Lawyers who use those proven fundamentals will also be the ones to use genAI in the smartest way. They will outpace the lawyers who just use AI.

Paradox 3: the grey cat effect

If lawyers who don’t use AI will perish, what will be the market differentiator among the survivors? Access to more powerful language models? Proprietary training data? Better prompt libraries?

Unlikely. New LLMs outperform older specialized ones. Open source alternatives and commoditisation will keep AI accessible and affordable to most. Hardware won’t be a moat either. Invidia have just unveiled a $3,000 personal AI supercomputer that looks like a Mac Mini and runs AI models with up to 200 billion parameters - making data center-class AI computing available to individual users. And everyone knows that prompt engineering is dead.

GenAI is a future that is being very quickly distributed and commoditised.

So the third paradox is the Grey Cat Effect: if lawyers who use AI will survive and those who don’t will die, the differentiator among the survivors will not be AI. In the black box of AI utopia, all cats are grey.

The differentiation for lawyers will come from things that are hard to acquire, develop and replicate. Things that offer a moat. The same things that differentiate good and bad now: usable advice, clarity, speed, smart pricing and the increasingly prized premium of interacting with decent human beings. In other words, a great user experience.

Achieving it requires nous, pragmatism, creativity, originality, authenticity, communication skills, and the ability to listen and make your clients laugh. These are much harder to come by than tech. But they can be learnt and developed.

Paradox 4: the disappearance effect

The simplistic trope is that all lawyers should use AI. But is that realistic? The harsh realities of the technology adoption lifecycle and pareto distribution, will tell you that some lawyers will use AI but most won’t.

GenAI will certainly change how we interface with software: through conversational prompts rather than menus and pre-configured workflows. If Microsoft’s CEO has it right, it could be much deeper than that: agentic AI working with back end systems in a way that collapses the notion of software applications (see this exploration of the topic by Alistair Maiden).

If AI eats the world, the distinction between "users" and "non-users" will be meaningless. We don’t say "lawyers who use the internet". AI will be integrated in the day-to-day tech stack and will be no more innovative than using the spell checker in Word. If the AI hawks are right, this normalisation - technological disappearance - will happen fast.

So the fourth paradox is the Disappearance Effect: those lawyers who use AI, will survive. The ones that don’t, will also survive.

Paradox 5: the Frankenstein constant

Users will always try to break the system and shortcut their way to answers. Whether that’s because of resource constraints, the law of least effort, the adequacy of “satisficing”, or the false comfort of knowing a little.

Before genAI, clients had Google and in-house lawyers had Practical Law. Start-ups frankensteined Ts and Cs off the internet. Nothing new under that sun.

So the fifth paradox is the Frankenstein Constant: clients’ tendency to shortcut their way to answers (whether using Google or genAI) might not be materially impacted by the extent to which lawyers use AI.

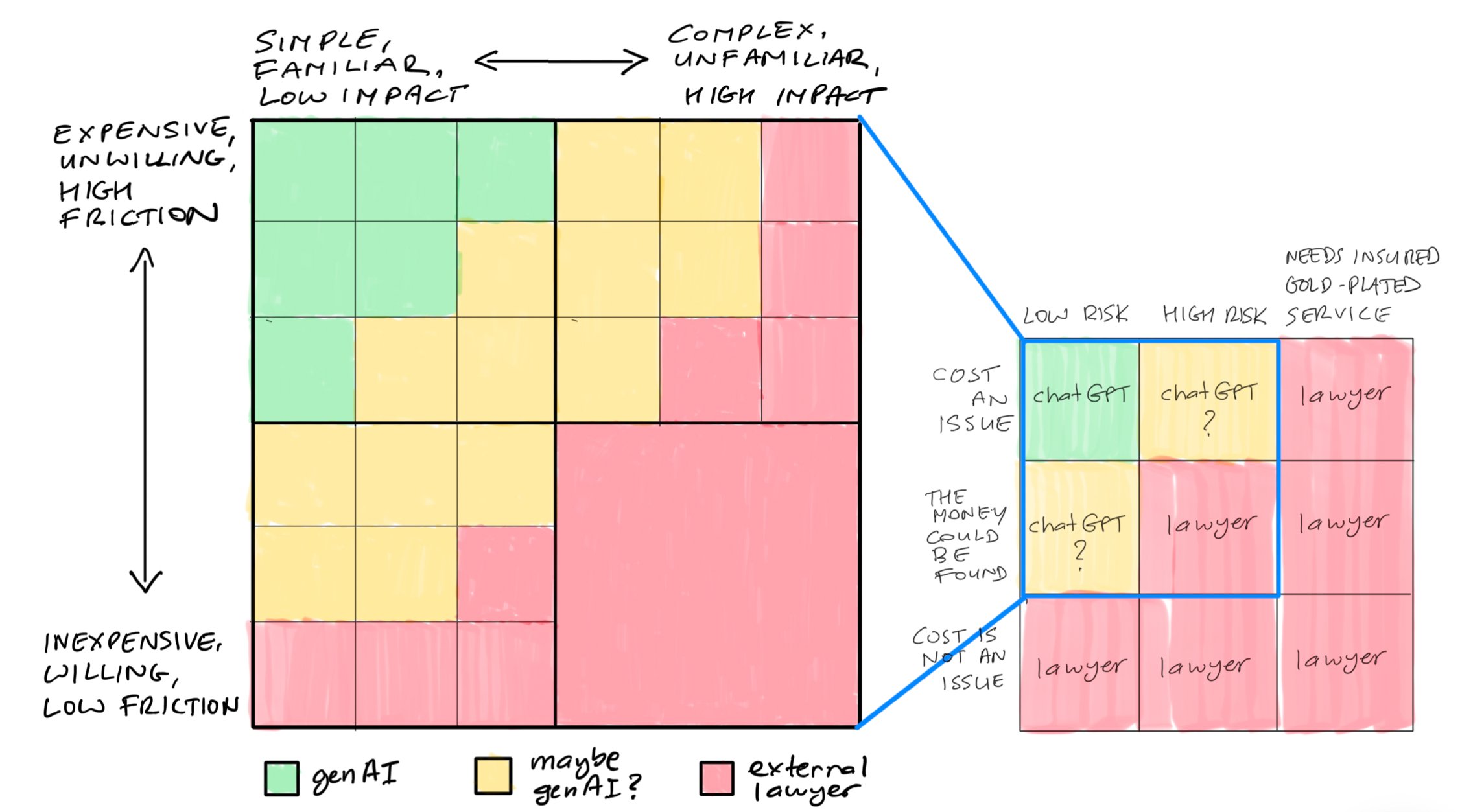

That’s because the drivers are fundamental things like time, budget and risk. I captured the notion using this chart, which shows the proclivity for businesses to use genAI (or a combination of genAI and Google, or just Google) versus instructing an external lawyer:

Unless genAI upends the cost/risk fundamentals, the basic topography won’t change.

There are two battlegrounds where the border might shift. The first, is in the process/transactional territory (where the value and risk is not in the legal component). That’s a complex battlefield already being fought with many players - it’s not a simple chatGPT vs lawyer equation.

The second battleground is the extent to which in-house teams can reduce their dependence on law firms, by agreeing with the business that it’s worth trading off the additional risk of genAI against speed and lower cost. It’s also the space where agentic AI could enable businesses to paint a portion of the process/transactional territory green. But legal service vendors that are more specialised and offer lower cost - plus assurance - are also playing in this space.

So the dynamics both expand and squeeze the green.

The first chart is an oversimplification, by definition. The north-west part of the territory can be described with a more granular view of “risk” and “cost”:

This view accepts that cost factors are several:

Expensive vs inexpensive - this is the price tag compared to other options available in the market, as well as perceived costliness.

Willingness to spend - based on urgency, perceived value and perhaps expected frequency of similar spend in the future.

Friction - how difficult it is to get budget approval and internal alignment, and the hassle involved in finding and instructing the right expert.

Equally, there’s more to risk:

Complexity - the actual or perceived complexity of the issue, including the extent to which the problem (or the service for resolving it) is a process/transactional one rather than one of legal interpretation.

Familiarity - the extent to which the client has done it before and their level of comfort with it.

Impact - the perceived impact for the business, and personal risks such as reputation and career.

The lawyers might find this graphic even more comforting! What I find interesting is the yellow space, where the legal service providers can battle it out.

Solving the paradoxes

What is clear is that genAI will force lawyers to deliver a better user experience to their clients.

The skill necessary to achieve that, is user-centric design, also known as design thinking. Legal design is the application of design thinking to legal documents, processes and services. It’s a mindset and a method.

Unless you are an instinctive genius (and some rainmakers are), you can’t design user-centric experiences without understanding and using design thinking.

Does genAI leapfrog legal design with its ability to extract, opine, explain to 5 year olds - and its uniquely conversational UX?

When I’ve talked to AI vendors, it’s pretty clear that good structured data and clear processes are key to making AI work. There’s unexplored opportunity for designing both source data and output.

Legal design is also one of several ways of skinning the efficiency cat. At Majoto, we’ve used plain language and visual design techniques to reduce time to contract by 80%. The oneNDA is a crowd-sourced standardised template that eliminates the need for negotiating NDAs. Both are examples of what can be achieved using legal design - even before you get to automation.

So there is plenty of opportunity for design - and design is only just starting.

Even more fundamentally: to build a business that achieves user centricity, you need to make user-centric strategic decisions as you navigate uncertain waters. You can’t do that without bringing design thinking into the very process of developing your business and technology strategy.

The take-aways for lawyers

The paradox hydra has one body: what does good lawyering look like in a genAI world?

If good lawyering means delivering what clients want (speed, quality, clarity, cost, a great experience), that means understanding what they want, and being able to deliver against it.

That’s why at Majoto we believe design thinking is a critical strategic tool, and the single most important skill that lawyers can learn this decade.

At Majoto, we use design thinking workouts to solve problems, and help legal teams deploy legal design in their work to achieve breakthrough results. We also teach legal teams to fish through our Design Lab concept. Get in touch with denis@majoto.io to learn more.